Retinitis Pigmentosa

Jump to: Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatments | Clinical Trials | Patient Registry | Research and Health Policy | Resources | References

Overview

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) describes a group of genetic disorders that damage light-sensitive cells in the retina, leading to gradual vision loss over time as the cells die off. While the condition is classified as a “rare disease,” it is one of the most common inherited diseases of the retina, affecting between 1 in 3500 to 1 in 4000 Canadians.[1] RP is often referred to as an inherited retinal disease, meaning that it is passed along genetic lines and inherited from one’s parents. Though it is usually diagnosed during childhood or adolescence, a minority of patients report symptoms later in life.

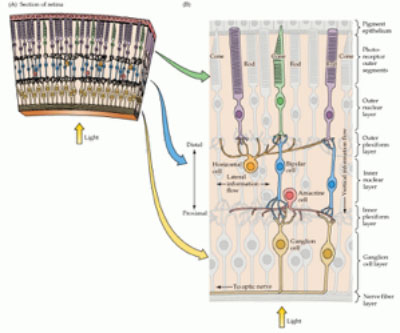

Specialized cells called photoreceptors are responsible for absorbing light and translating it into signals that are interpreted by the brain—it is these essential cells that gradually die off as a result of RP. The cells come in two varieties: rod cells and cone cells. Rod photoreceptors are responsible for peripheral and night vision, while cone photoreceptors are responsible for central, high-acuity vision as well as detail and colour. Since it is the rod cells that are first damaged by RP, peripheral and night vision are affected during the early stages of the disease, followed by a narrowing of the visual field, often referred to as a progressive form of “tunnel vision.” The death of rod cells eventually affects the cone cells as well, leading to the loss of central vision and often resulting, during the later stages of the disease, in near or total blindness. The length of this process varies from individual to individual.

RP was originally considered a single disease, but after decades of research—including research funded by FBC—we now know that there are several forms of RP and that these forms involve mutations in any one of more than 64 different genes. The gene or genes affected, determine the disease type and symptoms.

There are several different ways that RP can be inherited, which is usually described as the “inheritance pattern.” The different RP inheritance patterns include: autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and x-linked recessive. A genetic counsellor can talk with you about your family history and determine which of these patterns is associated with your vision loss. With this information, the genetic counsellor may be able to tell you more about how your condition will progress, and give you and your family information about the risks of vision loss for other family members. To learn more about genetic testing for RP, please consult our Genetic Testing Primer.

Typically, each person with RP only has damage in one pair of genes. Scientists have now identified more than 64 genes that can have mutations that cause RP. It is likely that mutations in more than 100 different genes will eventually be identified. Because so many RP-causing gene mutations are still unknown, there is about a 50:50 chance that genetic testing will provide a definitive result. Given your family history and the inheritance pattern of your RP, your genetic counsellor will be able to advise you about the likelihood that a genetic test will provide a definitive result.

Different genetic mutations can damage the retina or impair its function in different ways; for example, some mutations affect how the retina processes nutrients, while others damage the photoreceptors. It’s important to identify the specific gene and mutation, because many treatments being developed for RP will be for particular genetic types.

Symptoms

The most common early symptom of RP is difficultly seeing at night and in low-light conditions—this is called nyctalopia or “night blindness.” The loss of peripheral vision is also a common first symptom, and is often experienced alongside nyctalopia. As RP progresses, peripheral vision slowly diminishes, resulting in a narrow field of view or “tunnel vision.” By age 40, many people with RP are legally blind, with a severely constricted field of vision, although many may retain the ability to read and recognize faces. Uncomfortable sensitivity to light and glare is common, as is photopsia (seeing flashes of light or shimmering). RP can also cause a loss of visual acuity (the ability to see clearly), but the onset is more variable. Some patients retain normal visual acuity, even when their vision is reduced to a small central island; others lose acuity much earlier in the course of disease. Eventually, however, most people with RP will begin to lose central vision and some will lose all light perception.

Diagnosis

An ophthalmologist may suspect RP on the basis of a person’s symptoms and the findings of a simple eye examination. Two tests are used to clarify the diagnosis:

ERG (electroretinography): this is a test that measures the electrical responses of the retina to light, evaluating responses of both rod and cone photoreceptors. Although both rods and cones may be affected in people with RP, the most marked changes early in the disease are in the rod cells; this characteristic pattern helps diagnose the condition. The ERG test involves staying in a darkened room for 30 minutes, with drops put into the eye or eyes being tested. A special contact lens or gold-foil electrode is then placed on the eye or lower eyelid, and the eye is exposed to flashes of light.

Visual field test: this exam is designed to detect, measure, and monitor blind spots in vision. It involves looking into a device that emits flashes of light, with the patient asked to indicate which flashes can be seen. The flashes that are not seen are recorded. This gives a measure of how much vision is affected.

Genetic testing and counselling: Genetic testing and genetic counselling are an essential part of the diagnostic process. It can help determine the gene or genes that have been mutated, as well as the hereditary factors that are involved.

READ OUR GENETIC TESTING PRIMER

Existing Treatments

Currently, there is only a single approved treatment for a very rare form of RP on the market in the United States: a gene therapy called Luxturna, which can halt vision loss and even restore some sight in individuals with a biallelic mutation of their RPE65 gene (manifesting as either RP or Leber congenital amaurosis). Though the number of patients with this mutation is small, the medical effectiveness of Luxturna and its materialization as a pharmaceutical product demonstrate that there is significant potential for gene therapy to treat other forms of RP in the future.

READ OUR STORY ABOUT THE APPROVAL OF LUXTURNA

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are essential to the scientific process of developing new treatments: they test the viability and safety of experimental drugs and techniques, called “interventions,” on human beings. While there is no guarantee that enrolling in a clinical trial will provide any medical benefit, some patients do experience positive results after receiving an experimental therapy.

READ OUR CLINICAL TRIALS GUIDE

The website clinicaltrials.gov is a centralized database of clinical trials that are offered globally. But as the disclaimer on the site’s home page states, there is no guarantee that a listed trial has been evaluated or approved—the National Institutes of Health runs the site but does not vet its content. This means that there could be bogus or dangerous trials listed that are preying on patients. It is essential that you discuss a clinical trial with your ophthalmologist before enrolling, and that you pay close attention to enrollment criteria.

If you are interested in exploring what is available on the site you can click on the button below, which will take you to clinicaltrials.gov and initiate a search for trials relevant for patients living with RP.

CLINICAL TRIALS FOR RETINITIS PIGMENTOSA

Patient Registry

For individuals living with an inherited retinal disease (a disease caused by a genetic mutation), participation in a clinical trial could be a logical next-step (for a description of clinical trials, see above). But in Canada there is no centralized, guided mechanism for enrolling in a trial. With this in mind, Fighting Blindness Canada has developed a secure medical database of Canadian patients living with inherited retinal diseases. We call it the Patient Registry.

By enrolling in the Patient Registry, your information will become a part of this essential Canadian database that can be used to help connect you to a relevant clinical trial. The availability of relevant trials depends on a number of factors, so this tool provides no guarantees, but signing onto it will put you in a position to be connected to something appropriate. It is also a way of standing up and being counted: the more individuals enrolled in the Patient Registry, the better our chances of showing policymakers that there is a significant need for new treatments for inherited retinal diseases. The Patient Registry also helps to drive more sight-saving research!

You can begin the process of enrolling in the Patient Registry by clicking the button below.

Research Developments and Health Policy

Fighting Blindness Canada is committed to advancing the most promising sight-saving research, and has invested over $40 million into cutting-edge science and education since the organization was founded. Recognizing that science is tied to policy frameworks, FBC is also actively involved in health policy activities across Canada.

Many research groups are working to develop treatments and cures for RP. Experimental treatments can be divided into three broad categories:

- Protective Therapies

- Corrective Therapies

- Sight-Restoring Therapies

Protective therapies aim to stop (or at least slow) the damage caused by genetic mutations. Often protective therapies are not specific to one mutation, but may benefit people with many types of RP. These include treatments to stop the process of photoreceptor death (apoptosis), as well as cell-derived therapies that aim to help photoreceptors survive.

Some protective therapies aim specifically to prevent the death of cone cells in RP—and thus, the loss of central vision—in later stages of the disease.

Corrective therapies aim to reverse the underlying genetic defect that causes vision loss. If these therapies are successful they might prevent a person who is treated when first diagnosed, from ever developing vision loss. Corrective therapies might also help slow the disease in people whose vision has already been affected, especially in the earlier stages. The corrective therapies being developed now are specific to certain forms of recessively inherited RP. Gene therapies, which replace a non-functioning gene, are one type of corrective therapy. Clinical trials of gene therapies for several types of RP are underway, and the results so far are encouraging.

Sight-restoring therapies are also a growing area of research success. These therapies are intended for people who have already lost all, or much, of their vision. Stem cell therapies aim to replace the retina’s lost photoreceptors. There are promising early results with stem cell trials involving other retinal degenerative diseases; trials with RP are on the horizon. Retinal prosthetics, such as the Argus II or “Bionic Eye,” use computer technology to generate vision. Fighting Blindness Canada helped to support the first Canadian trial of the Argus II and continues to work closely with health policy experts across Canada to ensure that patients who could benefit from the Argus II device have access to this innovative treatment. Drug and gene therapies are also being developed that may give non-photoreceptor nerve cells in the retina the capacity to sense light.

Thanks to our generous donors, we are funding ground-breaking research in these areas. Click on the button below to review the full list of FBC-funded projects:

On the right side of this webpage, you will find an updating list of stories that detail new research and health policy developments relevant for individuals affected by RP.

Resources

Fighting Blindness Canada has developed additional resources that can be helpful in plotting an optimal path through vision care. Below is a link to our must read resources, including information on genetic testing, clinical trials and more, and a link to View Point (FBC’s virtual educational series).

VIEW POINT: VIRTUAL EDUCATIONAL SERIES

Health Information Line

Do you have questions about your eye health or information shared on this page? Our Health Information Line is here to support you.

References

[1] https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/retinitis-pigmentosa#statistics

Below is a basic video summary of retinitis pigmentosa:

Tell us what it’s like to live with RP.

Share your experience by filling out our survey using the button below.

Updated on September 8, 2020.

Join the Fight!

Learn how your support is helping to bring a future without blindness into focus! Be the first to learn about the latest breakthroughs in vision research and events in your community by subscribing to our e-newsletter that lands in inboxes the beginning of each month.